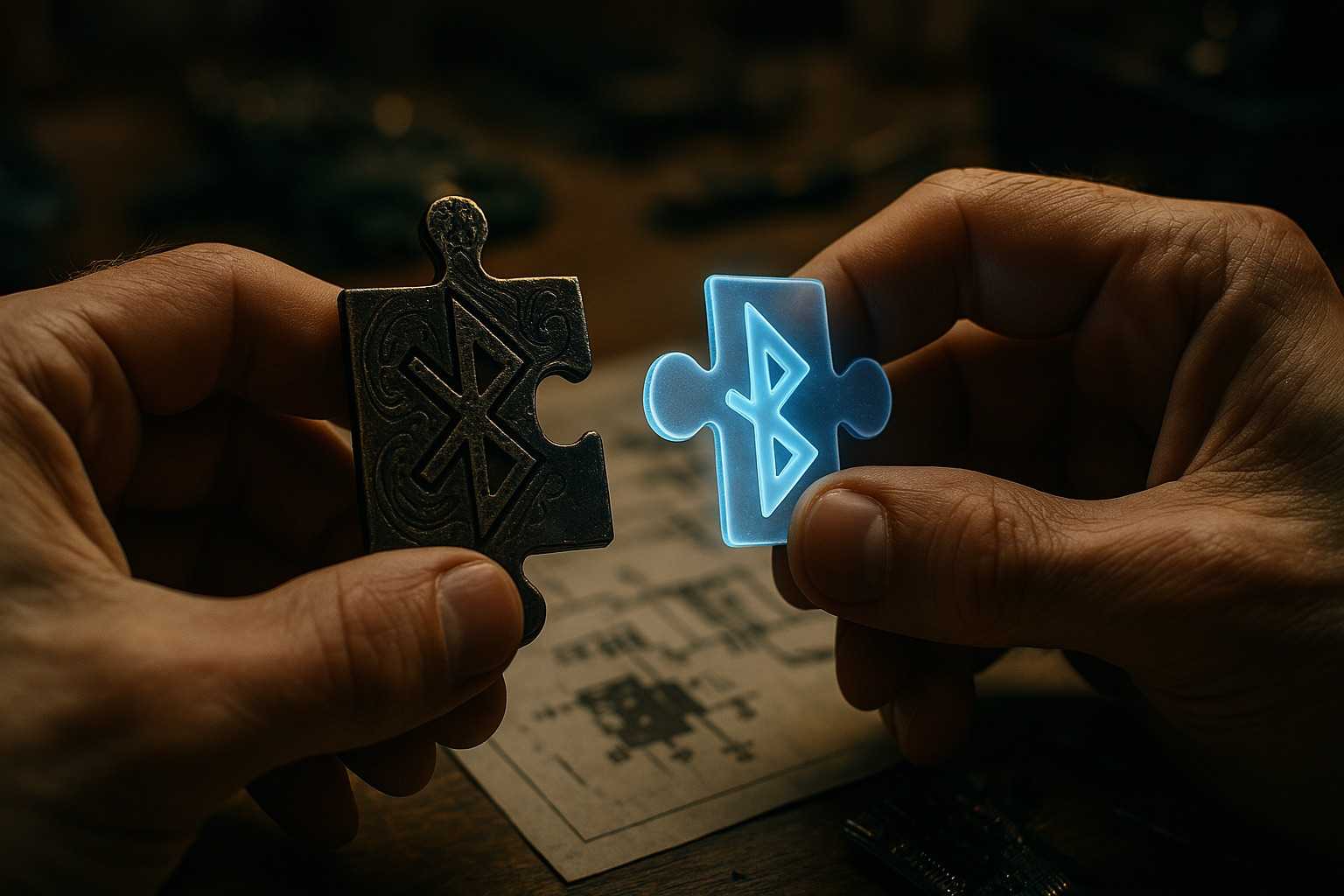

Developing software to interact with hardware often leads you down unexpected paths. While working on D2Explorer, aiming to provide an open way to connect the Huawei Watch D2 to Linux and macOS systems, we encountered a Bluetooth pairing process far removed from the standard procedures we initially anticipated. After successfully migrating our Bluetooth communication layer from BlueZ/D-Bus to the cross-platform SimpleBLE library, the next hurdle wasn't the library itself, but the intricate, proprietary handshake demanded by the watch. This journey became a fascinating case study in how custom protocols can create significant barriers and effectively lock users into a vendor's ecosystem.

The Expectation: Standard Bluetooth LE Pairing

Going into this, particularly after adopting SimpleBLE, the expectation was relatively straightforward:

- Use SimpleBLE to scan for the watch based on its advertised name (e.g., "HUAWEI WATCH D2-CA0").

- Initiate a connection using

peripheral.connect(). - If pairing/bonding is required (e.g., to access protected characteristics), SimpleBLE would ideally trigger the operating system's standard pairing mechanism (like a PIN prompt or Just Works confirmation managed by macOS or BlueZ).

- Once connected and paired/bonded at the OS level, we'd interact with standard or custom GATT services to exchange data.

This standard flow leverages the OS's Bluetooth stack for the core security and bonding, with the application focusing on GATT interactions.

The Reality: Huawei's Custom Application-Level Handshake

What we found, however, was entirely different. Establishing a basic BLE connection is merely the prelude. To actually authenticate the connection and gain access to meaningful data, the watch requires a complex, multi-step, application-level handshake orchestrated over custom GATT characteristics. Standard BLE pairing mechanisms seem insufficient or are bypassed entirely in favour of this proprietary flow.

The process, painstakingly reverse-engineered and implemented in D2Explorer's HuaweiPairingProtocol, looks roughly like this:

- Connect: Establish the basic BLE link.

- Enable Notifications: Immediately subscribe to notifications on a specific custom characteristic (

0000fe02-...). This is timing-critical. - GetLinkParams: Immediately send a custom command (Service ID

0x0001, Command ID0x0001) to the write characteristic (0000fe01-...). - Receive Server Nonce: Wait for a notification containing the watch's nonce (random challenge).

- Derive Secret Key: Generate a client nonce. Combine the server nonce, client nonce, and the numeric value from the watch's QR code. Use this combined data with HMAC-SHA256 (using the QR code value bytes as the key) to derive a shared

secretKey_. - AuthRequest: Send the client nonce and an HMAC digest (using the derived

secretKey_) back to the watch (Service0x0001, Command0x0002). - Verify Server Token: Receive a response containing the watch's authentication token. Verify this token using the derived

secretKey_and exchanged nonces. - SetTime: Send the current phone/computer time and timezone offset to the watch, encrypted with the

secretKey_(Service0x0002, Command0x0003). - QrToken: Send the original QR code value back to the watch, encrypted with the

secretKey_(Service0x0001, Command0x0004). - AuthResult: Send a final confirmation message, encrypted with the

secretKey_(Service0x0001, Command0x0005). - Authentication Complete: Only after successfully navigating all these steps is the connection considered authenticated by the watch.

This involves custom TLV (Type-Length-Value) message formats, CRC checks, specific service/command IDs, application-level encryption, and, as we discovered, extremely sensitive timing requirements, especially between connection, notification enabling, and sending the first command.

Why So Complicated? Vendor Lock-In by Design

The natural question arises: Why abandon standard, well-documented Bluetooth pairing for such a convoluted custom process? While Huawei might cite enhanced security, the practical effect is overwhelmingly vendor lock-in.

- High Barrier to Entry: This protocol is undocumented publicly. Reimplementing it requires significant reverse-engineering (analyzing official app traffic, firmware, or efforts like the Gadgetbridge project). This actively discourages third-party apps.

- No Interoperability: Forget using standard fitness apps or data aggregators. The watch will only complete its handshake with software that knows these specific secret steps – primarily Huawei's own Health app.

- Ecosystem Control: It forces users who want full functionality into the Huawei Health app and associated cloud services, making it harder to switch devices or platforms later.

- Reduced User Choice: Users seeking open-source alternatives or more privacy-focused solutions are essentially blocked unless the community undertakes the significant effort to decode and replicate the protocol, which is the very purpose of D2Explorer.

Bluetooth LE itself allows custom services, but this implementation goes far beyond defining custom data characteristics; it replaces the fundamental authentication mechanism with a proprietary gatekeeper.

The D2Explorer Effort: Rebuilding the Key

Our work on D2Explorer, therefore, shifted from simply using a BLE library to painstakingly reconstructing the client-side logic of this proprietary handshake. This involved:

- Implementing the specific TLV serialization/deserialization (

HuaweiProtocol). - Creating precise message builders (

ProtocolMessageBuilder). - Implementing the cryptographic steps (Nonce generation, HMAC-SHA256, XOR encryption) correctly (

CryptoOperations,CryptoUtils). - Managing the strict state transitions and timing (

HuaweiPairingProtocol,ProtocolStateManager). - Debugging failures often caused by millisecond-level timing mismatches or subtle crypto errors.

The D2Explorer application exists because of this complexity; it's the "workaround" necessary to achieve basic functionality outside the vendor's walled garden.

Conclusion

The Huawei Watch D2's pairing mechanism is a prime example of how custom application-level protocols over standard transports like BLE can be used to enforce vendor lock-in. While standard BLE pairing has its own nuances, the additional layers of custom cryptography, message formats, and strict timing imposed by Huawei create a significant barrier designed, intentionally or not, to keep users within their ecosystem.

Developing D2Explorer has been less about simply connecting Bluetooth devices and more about cryptographic detective work and precise protocol emulation. It underscores the value of open standards for interoperability and user choice in the connected device landscape. While we've managed to replicate the handshake, the effort involved highlights the hurdles placed in front of users and developers when companies prioritize proprietary control over open compatibility.

References

(Consider adding specific links or acknowledgements here if D2Explorer heavily relied on specific findings from other projects like Gadgetbridge)

- Gadgetbridge Project - An open-source Android application often involved in reverse-engineering wearable protocols. (Acknowledge if analysis was used)

- (Any other relevant technical blogs or findings used during development)

(Disclaimer: The analysis of protocol steps and cryptographic methods is based on the implementation within D2Explorer and external community analysis. Official Huawei documentation is not publicly available.)

Comments